Did my parents hurt my chances for success?

Tigard teachers weigh in on scientific links between student’s upbringing and future.

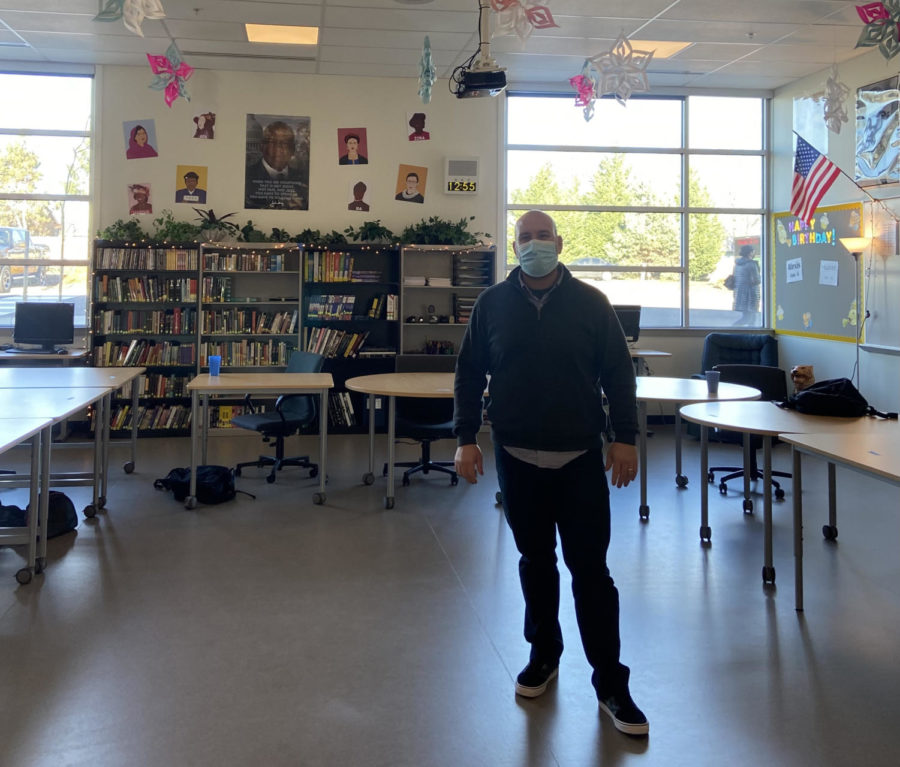

Michael Scher teaches CE2, which stands for Community Experience for Career Education. He doesn’t believe that parents hurt a students chance for success. He talked about the desire to succeed being intrinsic.

February 22, 2022

As humans, we tend to be a collection of our lived experiences and surroundings, even those we cannot control. Our actions, thoughts, and even personality traits are often influenced by our past and the experiences that surround us.

Links between success and upbringing ultimately leave many students questioning, “did my parents hurt my chances for success?”

According to an article in the American Journal of Public Health, an approximately twenty year study performed between Pennsylvania State and Duke University affirmed that the social skills exhibited by children as young as five years old could help predetermine their adult lives and success rates.

Near its completion, the study determined that kindergarteners with limited social skills were far more likely to struggle with addiction, commit crimes, require government assistance, and ultimately have lower success rates. However, those who exhibited good social skills, such as cooperation without prompting and understanding the feelings of their peers, were far more likely to attend college and have full-time jobs by the age of twenty-five.

Additionally, studies conducted by Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck, whose article “The Secret to Raising Smart Kids” appeared in Scientific American, show that the traits and learning behaviors exhibited by young students are heavily influenced by the ways in which they are praised. Her studies explain how “an overemphasis on intellect or talent—and the implication that such traits are innate and fixed—leaves people vulnerable to failure, fearful of challenges and unmotivated to learn,” again proving that the way children are raised can harm their ability to succeed.

One research funder of Penn State and Duke Universities studies, Kristin Schubert, states that the result of the study is to truly prove that helping children develop social and emotional skills is the most important thing anyone can do to prepare them for a healthy future.

U.S History teacher, Murray Carlisle, explains that he works hard to practice these principles of praise in the classroom, but primarily with his daughter at home.

In his home, he says praise and positive reinforcement are very important. That said, he focuses more on the hard work aspect of school, and tries not to overly praise for grades.

“We [don’t] pay her for any of the A’s, [don’t] do a special dinner, we just [praise] her,” Carlisle said.

He also explains that he doesn’t believe it is valuable to constantly tell children how smart they are.

Carlisle and other educators alike at Tigard High say their classroom experiences show however, that there can be exceptions to the scientific studies.

The CE2 Program at Tigard offers support to mostly upperclassmen for whom school is not a good fit. The goal of the program is to get and or keep students on track for graduation by providing them with individualized attention, career skills and training that will put them ahead in the working world post-high school. Michael Scher is one educator who works alongside these students. His office overlooks a vibrant class-like space and displays words of inspiration on posters all around.

After talking with Scher, it’s apparent that his opinions as an educator are genuinely shaped by his first-hand experiences with students. At various times, Scher brings up the word “intrinsic,” and explains that he is unsure that the motivation to succeed comes from upbringing, but rather it may be one’s innate attitude. As for the word “intrinsic,” it can be defined as “belonging to a thing by its very nature.”

“I have always had a strong internal desire to help others,” Scher said. “It has always given me a sense of purpose to support students in finding their own positive pathway in their life.”

Growing up, Scher’s mother was a teacher, which he says may be what initially pushed him into the field. Additionally, he shares a classroom experience which also appears to be where his drive for education comes from.

“I remember sitting in seventh grade English class and thinking to myself that I could do a better job teaching the class than the old lady (who had been a teacher at the school for the last 25 years) was doing at the time,” Scher recalled. “Kind of a weird thought for a 12 year old, but it stayed with me.”

In an interview, he goes on to question whether or not upbringing is a contributing factor of a child’s success altogether.

“I’ve seen kids on both sides of the spectrum,” he said. “Kids that have parents and support networks that are deep and are really there, and that kid for whatever reason, decides that that’s not working for them.”

“If they don’t have the work ethic, if they don’t see it, if it’s not intrinsic to them then chances are [they’ll] stay in that one spot and keep spinning [their] wheels.” Scher adds.

While these ideas are shared and understood between many educators alike, the individual experiences of the teacher differ these opinions from person to person.

Carlisle explains that although he finds truth in the studies, upbringing doesn’t tell the whole story for him either. He explains that he believes situations that confront a child with hardship can even be beneficial with enough cognizance and maturity.

“I’ve seen students who overcome [familial issues] and work hard and not only pass my course, but do well in the course,” Carlisle explained. “They have resilience and grit and determination and they’re able to push through and be academically successful… I think [challenge and difficulty] can build that grit.”

It’s clear that the common ground between these teachers and many others, is the belief that anyone can succeed and their drive to help students do just that.