Terms and censorship

Bonifacio Yuzon weighs in on the ethics of censorship in the age of modern media.

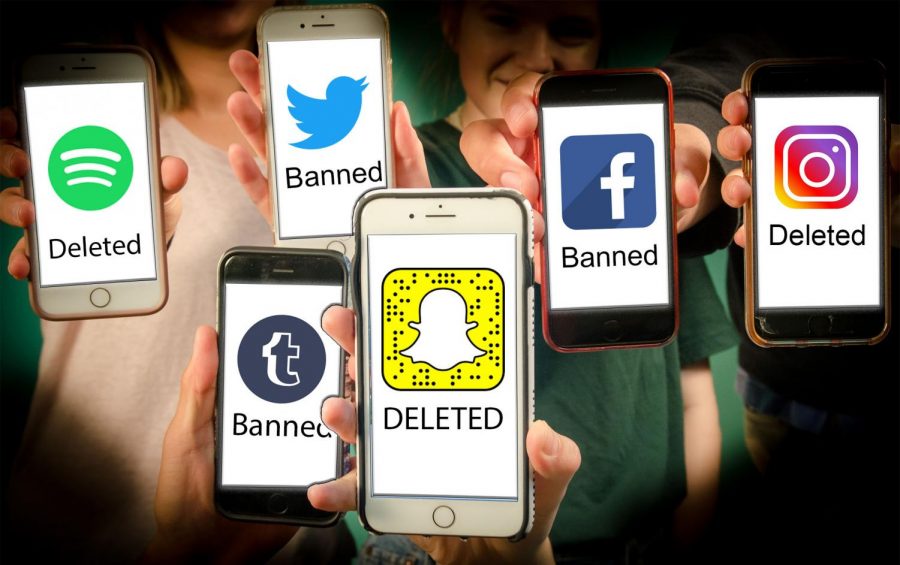

Tim Galvan, Photo Illustration

What happens when a social media company has the right to determine what you can and cannnot say?

September 28, 2018

Although the First Amendment guarantees free speech to all citizens, this is not the case when it comes to social media.

Almost all social media networks nowadays require that users agree to their terms and conditions regarding proper usage. These policies condemn impersonation, spam, harassment, pornography, threats of violence, and other aggressive or inappropriate behavior. Most social networks also suspend users for anything labeled as “hate speech” or discriminatory talk against other people based on race, gender, or other personal traits.

These terms are meant to uphold the mission statement each medium claims to promote, which is the maintenance of civility in online discussion. Monitoring social media is a very important task as it protects people from malicious content so they can safely continue to socialize and interface on the platform. But it is also crucial where social networks draw the line on what is and is not hate speech, as this distinction gives them the power to decide which posts to keep up and which to delete.

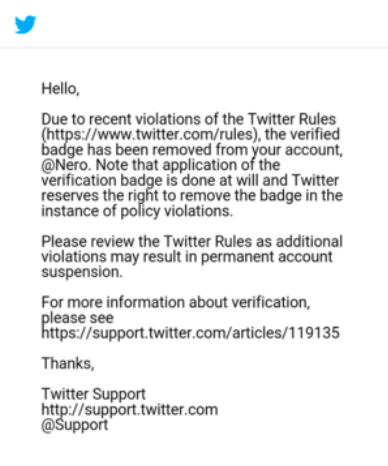

Infowars, a heavily conservative-leaning podcast, recently had their accounts deleted from Twitter, Youtube, Facebook and Spotify for numerous violations of these platforms’ terms and conditions regarding ‘hate speech.’ This drew mixed reactions online, although most people were not concerned for Infowars itself. After all, Infowars’ incendiary publishing has been very offensive toward transgender people, immigrants, and countless other minorities. In addition, Infowars speaker Alex Jones was sued for attempted defamation after creating a conspiracy theory relating to the Sandy Hook shooting. It should surprise nobody that Infowars’ restriction of access to social media was well-deserved, but the bans bring up the question of what role social media should play in how people express their opinions.

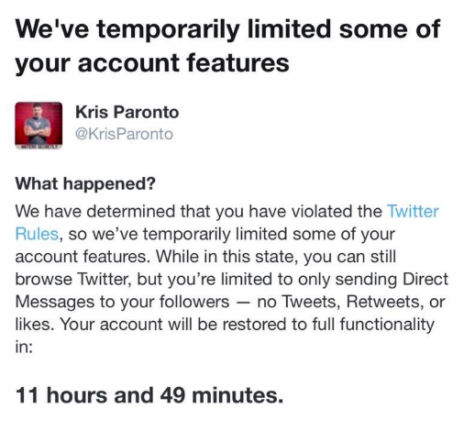

Another more reasonable issue worth concern is the controversy surrounding Army Veteran Kris Paronto’s Twitter account, which was suspended twice in quick succession. Paronto angrily responded to another Twitter user’s comment, calling the commenter “an idiot” for claiming that Barack Obama was directly responsible for the killing of Osama Bin Laden.

On Sept. 7, Paronto’s account was suspended for his speech, and he agreed to take down the offensive tweet in order to regain use of his account. However, Paronto later posted a screenshot of his original tweet in a follow-up post, which resulted in a second suspension.

Paronto’s political opinions have historically been outspoken, and his distaste for liberalism and heavy criticism of Obama certainly tend to draw the attention of people who disagree. Critics of Twitter’s suspension of Paronto complained of a bias against conservatives and right-leaning Twitter users.

The possibility of a bias against right-wing media users must be recognized should Twitter and other social networks retain their current ability to censor voices on their own accord.

Of course, private companies and institutions have the right to delete and edit what is said and discussed on their websites. A social medium should not be forced to display any message against its will. However, it must also be considered that these social media networks do not monitor free speech in the way our Constitution declares, but in a way that most benefits them and impacts how a message is distributed.

The same applies to Internet providers, especially now that net neutrality has been lifted. This gives an immense amount of power to the companies who provide their users with Internet, since they now have the ability to restrict certain websites according to their interior motives.

While no serious threats to free speech by social media companies currently exist, some could easily arise in the future. Businesses that seek the greatest profit will always do what is most advantageous to them. If promoting free speech is most profitable, then that is what businesses will do. If censoring certain ideas seems like a better plan, businesses will naturally pursue that plan. Just because the government will not abridge our speech does not mean corporations will hesitate to act in their own interest.