Hi-Spots article on air quality prompts close look at TTAD pools

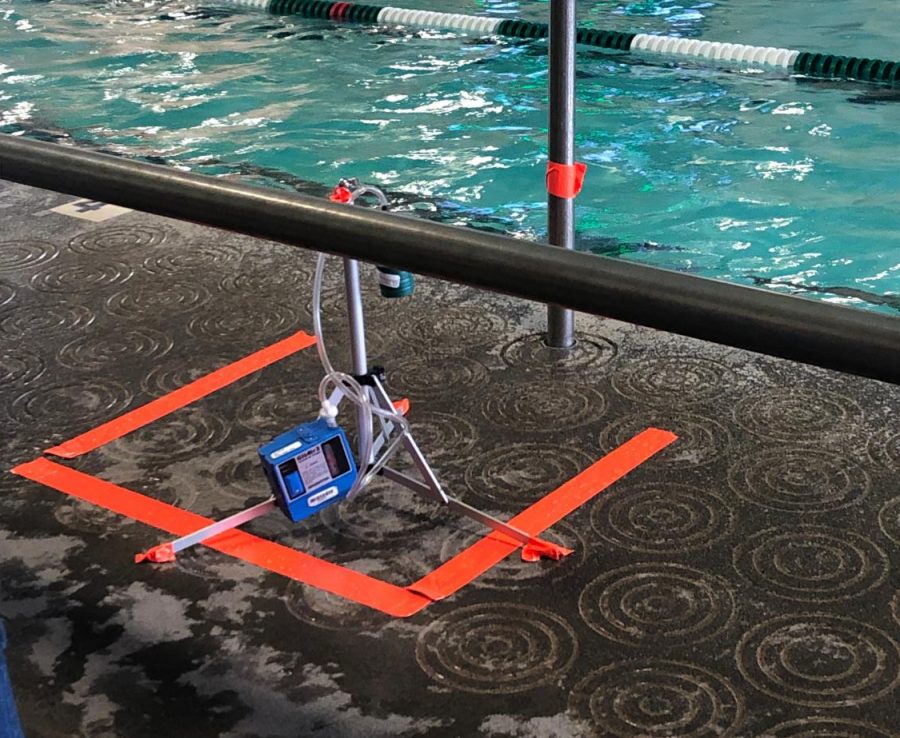

TRC Solutions tested the air quality in the swim center on the Jan. 24 meet against Lake Oswego. They were testing for trichloramine levels, which can cause breathing problems in pool houses if the level get too high.

March 1, 2019

An opinion piece in the January edition of Hi-Spots, Swim center air quality needs to be addressed, called upon the Tigard Tualatin Aquatic District to look into the air quality at the Tigard Pool based on the high rate of asthma and breathing complaints among the high school team’s swimmers.

This story brought to light a possible asthma problem at the Tigard pool house, and called upon TTAD and OSAA to make changes and keep students safe. Since then, the school district, along with the aquatic district, have taken steps to find out if there really is a problem.

While the swimmers themselves had been commenting on the high rates of asthma and complaining about how hard it was to breathe during practice, the conversation had mostly stayed amongst the swimmers. These complaints hadn’t made it to school district officials. Darin Barnard, the Director of Operations for the Tigard Tualatin School District, found out about the problem by reading the article in Hi-Spots, on the day the paper was distributed.

“I first heard about the problem when the paper came out,” Barnard said, “It’s concerning if it has been going on for a long time.” The pool manager for the TTAD pools, Anthony Markey, also found out that athletes had been complaining only after the article came out.

After learning of the problem, Barnard took immediate action. After receiving the paper on Thursday, he met with TTAD on Friday. Barnard explained that technically the school district and the aquatic district are separate entities. Around 2010, TTAD took control of the school district pools because it wasn’t economically advantageous for the school district to keep the pools running. TTAD leases the building from the district for $1 a year. Even though the pools are on district property, TTAD is a separate entity from the school district itself.

TTAD and the school district are working together to answer two questions. One, what is the state of the air quality at the pool? And, two, what can be done to improve it?

“We don’t want anyone to get sick,” TTAD Board President Kathy Stallkamp said. She was among the people present during the meeting with Barnard. “The safety of everyone–students, people watching–is super important to us.”

To answer the first question, those from the school district and the aquatic district met up with insurance company members that next Monday. There, they created an air quality plan. Part of the plan included testing the air quality during a swim meet, when the activity in the pool house would be highest.

During the Jan. 24 home meet against Lake Oswego, TRC Solutions, an engineering, consulting, and construction management company, set up air quality testers in three different places around the pool house. These were placed near the water, at standard breathing level, and above breathing level. This way they could get the full scope of what was going on. Additionally, they did this same type of testing at the Tualatin pool.

What they were specifically testing for was the trichloramine levels present in the air. Trichloramine is the gas that’s released when chlorine and other organic matter bind together in the pool, releasing the smell that is recognizable when walking into many pool houses. The higher the trichloramine levels, the more potent the smell and the higher probability of being unhealthy.

“We wanted to test it at a real meet, when there’s a crowd in the pool, not when no one’s in the pool,” Barnard said, “When you test it on a weekend or at night, it wouldn’t work.”

Results came back on Feb. 8

There are not many exposure limits set for trichloramine levels. There is no occupational exposure limit (OEL) or threshold limit value (TLV), but Barnard explained that the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that trichloramine levels should not exceed 500 µg per m3. Since the WHO recommends the levels not exceed 500, the school district wanted to make sure their levels were below that number.

Out of the eight total samples, three came back signifying trichloramine levels higher than the WHO recommendation. At the Tigard pool, at breathing height near the deck, the levels were at 520 µg per m3. This is where swimmers either start/stop their events, or hang around with their fellow teammates after their sets. This makes sense as to why the trichloramine levels would be higher there; a higher concentration of students, the more chlorine stays in the air.

The other two samples came from the Tualatin pool. In the middle of the bleachers, the level reached 520 µg per m3. This is for all around the pool-–where the spectators watch, and on the deck. Additionally, when testing near the water, one of the samples reached 600 µg per m3. That means, when swimmers turn their heads to breathe during strokes, they are breathing in trichloramine levels that are 100 µg per m3 higher than the recommended WHO limit. That result was particularly concerning and worth further testing.

Now they’ve answered the question about the quality of the air, they still have one more question left. What can be done to improve it?

They’ve already implemented new practices to reduce the trichloramine levels in the pool. Now, all swimmers must take a shower before and after getting in the pool. This has already been a practice at the pool, but has not been as strictly enforced as it is now.

“We’re really enforcing showering before getting into the pool now,” Barnard said, “We want to control what additional chemicals are going into the pool.”

Additionally, Anthony Markey, the TTAD pool manager, made sure the air handling system (HVAC) was inspected and calibrated. No issues were found.

“Both the Tigard and Tualatin pools have passed every Oregon Health Authority inspection since I started at the pool. As far as I know we have had a clean record with the state of Oregon.” Markey said.

According to Washington County’s website, environmental health experts at the Health Authority inspections, which are only conducted twice a year for year-round pools, check for chemical treatment and proper operation of and maintenance of the filtration system. They do not test for air quality.

The Vu siblings, who both swim on the club and high school teams, think there has been a change since the school district and aquatic center became aware there was a problem.

“The air quality has been better I feel like,” freshman swimmer Noah Vu said.

He and his sister, Emma, have a personal connection to the topic of air quality. Emma, his older sister, was diagnosed with chlorine-induced asthma during the swim season. This inspired him to bring this issue to the Publications staff, and Noah even helped write the previous opinion piece.

“A few [club] practices ago I saw a lady monitoring the air quality during the whole practice,” Vu said.

At the district level and not the TTAD level, Barnard believes some athlete health tracking would be a good idea.

If coaches are aware of kids with health issues, such as those with chlorine-induced asthma, they should be reporting that to the athletic trainers as well.

Stan Corcoran, a swim coach and pool manager at McCallie School for Boys in Chattanooga, Tennessee, has some suggestions for what the Tigard and Tualatin pool houses could do to improve athlete safety as well. Corcoran’s pool had air quality problems too. They traced the problems back to their air system not being designed for their 12-lane swimming pool. He stressed the importance of finding a system to work with the pool being used, as it provides fresh air, which dilutes the concentration of trichloramines and improves the air quality.

He also recommended a specific product, the Paddock Evacuator, a fan that blows across the surface of the water. This blows off the assorted chemicals on the surface of the water, allowing for safer breaths in between strokes. However, he mentioned that fans can work just as well and are less expensive.

“Best thing you can do is get a new system, turn on fans, blowing air on the surface of the pool, and open the door when the air gets bad,” Corcoran said.

Now that TTSD and TTAD are aware there might be a problem, they are studying what to do to keep everyone who uses the pool safe. High school swim season may be over, but the pools are still in use.